|

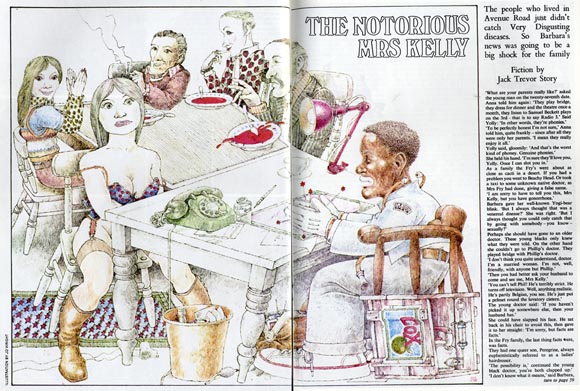

The people who lived in Avenue Road

just didn't catch Very Disgusting diseases. So Barbara's news was going

to be a big shock for the family.

Fiction by

Jack Trevor Story

`What are your parents really

like?' asked the young man on the twenty-seventh date.

Anna told him again:

'They play bridge, they dress for dinner and the theatre once a month,

they listen to Samuel Beckett plays on the 3rd—that is to say Radio 3.'

Said Yolly : 'In

other words, they're phonies.'

`To

be perfectly honest I'm not sure,' Anna told him, quite frankly—since

after all they were only her parents. 'I mean they really enjoy it all.'

Yolly

said, gloomily: 'And that's the worst kind of phoney. Genuine phonies.'

She

held his hand. 'I'm sure they'll love you, Yolly. Once I can slot you

in.'

- - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - -

As a family the Frys were about

as close as cacti in a desert. If you had a problem you went to Beachy

Head. Or took a taxi to some unknown native doctor, as Mrs Fry had done,

giving a false name.

`I am

sorry to have to tell you this, Mrs Kelly, but you have gonorrhoea.'

Barbara gave her well-known Yogi Bear blink. 'But I always thought that

was a venereal disease?' She was right. 'But I always thought you could

only catch that by going with somebody—you know—sexually?'

Perhaps she should have gone to an older doctor. These young blacks only

knew what they were told. On the other hand she couldn't go to Phillip's

doctor. They played bridge with Phillip's doctor.

`I

don't think you quite understand, doctor. I'm a married woman. I'm not,

well, friendly, with anyone but Phillip.'

`Then

you had better ask your husband to come and see me, Mrs Kelly.'

`You

can't tell Phil! He's terribly strict. He turns off television. Well,

anything realistic. He's partly Belgian, you see. He's just put a pelmet

round the lavatory cistern.'

The

young doctor said: 'If you haven't picked it up somewhere else, then

your husband has.'

She

could have slapped his face. He sat back in his chair to avoid this,

then gave it to her straight : 'I'm sorry, but facts are facts.'

In

the Fry family, the last thing facts ever were, was facts.

They

had one queer son, Peregrine, always euphemistically referred to as a

ladies' hairdresser.

`The

possibility is,' continued the young black doctor, ‘you're both clapped

up.'

`I

don't know what it means,' said Barbara, `but I can't accept it. I want

a second opinion. I'd like to get dressed now.'

The

young black doctor never could work out why they got undressed. He gave

it a moment's thought after she'd gone, wondered if perhaps she was his

bank manager's wife; why she had given him a false name.

- - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - -

`Can I bring Yolly in tonight?'

asked Anna. `No, you can't,' she replied to herself as her mother was

attacking something on the chopping board as if it were an enemy.

`Who's Yolly?' Barbara asked, letting the last bit of carrot fly across

the kitchen.

Anna

told her all about Yolly again. They'd soon be having their silver

anniversary and he hadn't met any of the family yet. 'It's starting to

sound really Gothic, all these excuses to keep him away from Avenue

Road. He thinks you're lepers or something.'

Barbara blinked again. A most unfortunate exaggeration under the

circumstances. Gonorrhoea in Avenue Road was worse than leprosy,

especially amongst middle-aged parents. Two heads would have been more

acceptable. 'I'm afraid you have another head growing from your left

ear, Mrs Kelly.'

`Are

you avoiding the question, Mummy. Or just talking to yourself?'

`I am

preparing a salad, Anna.' That's another thing you do in a disconnected

family is prepare salads. And, when bored, Barbara counted things -

radishes, washing up, laundry, hair-rollers, lamp-posts, years . . .

'Bring him another night, darling. Tonight I've got something very

serious to discuss with your father.'

`Who

- Phillip?' asked Anna. You couldn't talk to Phillip Fry except on the

telephone. If you were face to face with him he did this thing of

cupping his right ear with his hand and talking into his sleeve. You

watch any advertising space salesman conducting a conversation with his

family. 'Hello, there . ..’

Anna

said: 'Funnily enough, Daddy has something very serious to discuss with

you.' `Oh God,' thought Barbara, 'and Jesus Christ. Did that mean the

diagnosis was right? That Phillip had also consulted a young wog doctor

in a little-used part of town? "Ask your wife to come in and see me, Mr

Kelly . . ." '

`What's so important? What's happened? Stop chopping up carrots, Mummy!

It looks so symbolic!'

Barbara started on the onions, which are always good for disguising

emotion. She was going to have to watch it. Both the kids were very

strait-laced. Well, as far as she knew, which was not very far. She

didn't quite know what Anna did with Yolly but certainly Peregrine had

got rid of his rabbits as soon as he reached puberty. `Can I make my

mayonnaise?' Anna was asking.

`You

can make whatever it is you make.' The problem was immense. She hadn't

been with anyone else and Phillip's most intimate relationships were

conducted on the phone.

Could

you get VD on the phone? Young people knew more about these things. She

was going to need help and it needed great delicacy and tact. She said :

`Do you think your father has sexual intercourse with other women?'

`Don't ask me questions when I'm adjusting the gas. I don't know. How

the devil should I know?'

If

Anna didn't know anything then Peregrine wouldn't know. 'What's this

boy-friend of yours really like?'

Anna, who had adjusted the North

Sea gas to a barely finite level, now put it out. `Damn. Now you ask me.

I'm surprised you know he's a boy and not a girl. We have some very

strange tendencies in this family. Yolly is young and handsome

underneath it all—you know, the hair and stuff. And he's very

philosophical.'

`Make

enough mayonnaise for Yolly,' Barbara said, reaching a decision.

- - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - -

`Daddy, this is Yolly, this is

Mummy, this is my mayonnaise.'

`Good

evening, Mr Fry,' said Yolly. `

`We'll wait for Peregrine,' said Barbara Fry.

`Peregrine won't be coming tonight,' her husband told her, holding his

ear.

`But

it's his laundry night,' she reminded him. Phillip Fry said: 'Not any

more. I don't think Peregrine should expect you to do his laundry. It's

time we told him. I wanted a serious discussion. I thought we'd be

alone.' And he hung up on the subject by simply putting his receiver

hand back on the arm of his chair.

`You

see?' Anna said, to her mother. 'It's not another woman at all.'

Yolly

said : 'Would you rather I came another night?'

Anna

pushed him onto the settee. 'Of course they would. Quickly, tell them

I'm pregnant, then at least you can stay to dinner.'

Barbara said: 'But I like doing his washing. It's all I've got left of

him.' Then she said:`Besides, I've got VD. I want him here.'

Phillip Fry peered at his wife and daughter and the strange young man,

hoping they would disappear.

`I

say, is that right?' Yolly asked, brightly. It was the first bit of

conversation that rang normal bells with him and he became animated.

'Have you caught a dose, Mrs F? That's jolly rotten luck.'

`Don't be silly,' Anna said. 'She's just trying to attract attention to

herself. How would Mummy catch VD except from Daddy? And how would Daddy

catch VD?'

Phillip Fry's soup spoon crashed into the bowl and red polka dots

appeared like measles in a Marx Brothers' film all over Barbara's face.

She wanted to remove them but felt that they were oddly appropriate

until the subject had been properly aired.

Before this happened Peregrine came in with his hairdressing partner

Kenneth. `I told you not to come,' his father said, swerving his

frustrations to something more important than dirty talk.

'Correction, Daddy,' said Peregrine. 'You told me not to bring my

smalls. Well don't worry -Kenneth is doing them for me. Phew, it's ever

so warm in here.'

Peregrine was holding a poodle

under his arm. Peregrine was dressed in green flared

trousers and a contrasting green

high-necked woollen jumper. Sharing a secret communion of opinion, Yolly

went cross-eyed at Anna who blamed it all on God. Kenneth kissed

everybody including Mr Fry and then said to Barbara: 'And what were we

doing at that doctor's this afternoon?'

Everybody looked at Mummy. To her daughter, suddenly the day became

clear, spots and all. 'You're preggers, Mummy! We're going to have a

belated little stranger!'

`Is

this true, Barbara?' Phillip Fry asked, in justified surprise.

`Don't tell them, darling,' Peregrine told his mother. To the others he

said: 'It's female, private, and personal. If you must know, I sent

her.' And to Barbara: 'That doctor's ever so good, isn't he? He injected

my piles. That's how I met him. Oh, and he gives Kenneth his drops…

doesn't that sound awful!' Then, hungrily: `Mmm! Something smells nice .

..' As he sat down to eat he pressed his mother's arm and gave her a

confidential, womanly smile: 'What did he say, dear?'

`I've

got VD,' Barbara told her family again. Suddenly it didn't seem any

worse than having a son like Peregrine. `Gonorrhoea, in fact,' she

added, as though to give it a little status.

Phillip said: 'Must we have that dog at the table?'

There

was a moment during the war that Barbara remembered when the engine of a

doodle-bug bomb cut out directly over a Lyons' tea shop in Sloane

Square. Nobody moved, but nobody ate.

`The

doctor wants to talk to you about it, Phillip,' she said.

Phillip Fry went on the phone and came off, tried to make them vanish

and failed, then finally said: 'Did you say VD, dear?'

`Yes.

V for very, D for disgusting. Venereal disease.'

Anna

said: 'I'll put the dog in the kitchen.'

`No

no,' Peregrine said. 'He's all right, he doesn't understand yet.'

To

Yolly, as a long-banned outsider, the subject seemed surprisingly human.

'Soon get rid of it, Mrs Fry. Trot along to the clinic – have to lay off

the booze for a bit . . . '

`Yolly

. . . ' said his young mistress. Peregrine unaccountably turned to the

visitor and shook his hand. 'And where did you two meet?'

Phillip Fry said: 'Why didn't you go to Dick Yates? He's your doctor.'

`He's

Avenue Road's doctor,' Barbara said. And although no-one had questioned

it, she said: 'I'm not angry. If you've been having affairs, Phillip,

it's your business. Giving me VD is my business. Who was it?'

`There's been nobody else but you, Barbara.'

`I

don't believe you,' said Barbara.

Phillip said: 'And I don't believe you. I want a divorce.'

Peregrine said: 'Oo, we are cross!' He started eating.

- - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - -

The great mistake Mrs Barbara

Fry made was in wearing a leopard fur coat in front of a judge who was a

prominent member of the Wildlife Trust Fund. The evidence was relatively

immaterial.

`And

did your wife come to you and confess that she had contracted venereal

disease?'

`She

did, yes.'

`Was

this in the presence of witnesses?'

`It

was, yes.'

`Were

you shocked and horrified by the nature of her – ahem – illness?'

`I

was, yes.'

`And

did your wife suggest that she had contracted venereal disease from

you?'

`Yes,

she did.'

`And

did you subsequently visit a doctor and have certain tests made?'

`Yes,

sir.'

`And

what were the results of those tests?'

`Negative, sir.'

`In

other words, she had VD and you did not.'

`That's right, sir, yes.'

It was a full court following

unusual public interest and a good deal of wet weather.

`How

do you explain your immunity?'

`We

had not made love for two months. Not since my pneumonia. Barbara must

have picked it up during that time.'

`Was

your wife in the habit of "picking things up" Mr Fry?'

`I

don't know, sir. It came as a surprise. She went to a different doctor

and gave a false name. Mrs Kelly.'

`Did

you get the impression that your wife was leading a double life?'

`I

did, sir, yes. The doctor was black, for one thing. He had a mangle in

his consulting room. He criticized our married life. Very impertinent.

He said that my wife was frustrated. She undressed to have a urine test

and then she undressed to hear the result. That was while she was Mrs

Kelly, of course.'

Phillip made a good witness. When he wasn't cupping his ear and talking

into his cuff, giving the endearing impression of old age, he was

dialling telephone numbers in the dust of the witness stand ledge, as if

totally bereft and broken if not actually insane.

`Now

I want you to answer this with utter frankness, Mr Fry. Have you ever

had sexual relations with a woman not your wife?'

`No,

sir, never ever …’

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

As

you know, no drinking, advertising man can make such a statement with

any degree of accuracy. Phillip Fry, who had spent twenty years helping

to create the cloud-cuckoo land of consumer goods advertising, had a

special gift for making reality disappear. One of these realities was

the girl who came into his office to clean his telephone some months

after his family had successfully broken up.

`Good

morning!' she sang. This rang no bells for Phillip.

'Shall I give your equipment a little rub up?'

This

rang bells. Christmas, was it? Or Easter? Or somebody's leaving party?

He seemed to remember a bottle of Pernod in the goods-lift with an 'out

of order' sign on the doors to keep out intruders. This didn't sound

like him. He was very slow at making overtures.

`It's

all right. Don't move. I can manage. . . '

Good

grief. It all came rising up again as she slid between him and the desk.

'You look ever so sad,' she said.

Well,

he was sad. Everybody appeared to have come out of the divorce in good

shape except himself. `Mrs Kelly' was now a flourishing boutique in

Market Street, run by Peregrine, Barbara and Kenneth. Anna and Yolly

were living somewhere on the borders of sin and domesticity. Only

Phillip had landed in the lonely desert of middle-age. Still, it wasn't

too late to ring Barbara now and make a full confession and apology.

Salvage something of what they had had.

`Wait

a minute. Let me get rid of all the nasty germs. 'scuse my legs . . . '

But

what had they had in Avenue Road? Nothing quite like this.

`So

what are you doing tonight?' he asked her.

`What

about your wife?'

`Oh,

that's all finished and done with. She let me down rather badly in fact

. . . '

After a time, without much

difficulty, he came to believe this. You'll find him in the Coach and

Horses, or sometimes in a drinking club in Rupert Street talking to that

chap who forges Equity cards for aspiring actress dollies.

Oh,

it's a true story, of course. Only the names have been changed to

protect the guilty.

|